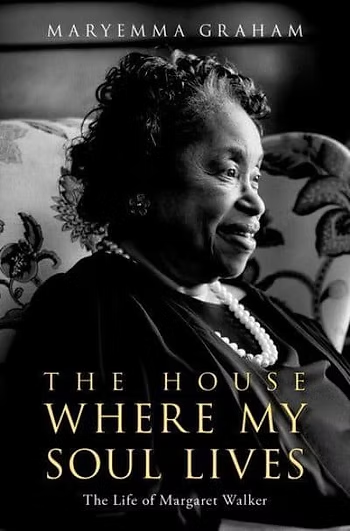

If you wait twenty years for something, you figure the payoff should be special. It is indeed if you read Maryemma Graham’s massive biography of Margaret Walker, The House Where My Soul Lives. An absolute artist of the archive, Graham has provided a definitive “life” of a major, if not always properly acknowledged, literary and cultural figure of the twentieth century.

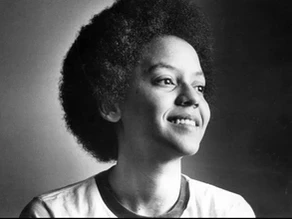

A free-spirited, outspoken, and often willful child—even while sickly and frail—Walker knew from childhood that she wanted to become a writer and kept journals beginning at a young age. Therefore, we see glimpses of her early drive to master poetic forms and to live an exemplary life in line with her firm spiritual commitments. The trail is never an easy one for Walker; she continually battled poor physical and mental health. But determination emerges as perhaps her strongest trait. Graham masterfully charts the journey from Walker’s 1915 birth in Birmingham, Alabama, to her coming of age in New Orleans, which included meeting Langston Hughes, to her graduation from Northwestern University in 1935. By then, she was close to publishing her signature poem “For My People” and had drafted 300 pages of what would become Jubilee, a historical novel published three decades later. During the 1930s, Walker also worked on the Federal Writers’ Project in Chicago and was the central energy, a point not often made in scholarship but a point Graham makes clear, in the South Side Writers Group, which included Richard Wright, Arna Bontemps, Frank Marshall Davis, Marian Minus, and Fern Gayden.

Of course, most readers familiar with Walker will be anxious to read about the failed Walker-Wright friendship, which ultimately served Wright better in literary terms than it did Walker. Walker even suggests that her own writing is the source of the opening scene of Native Son. However, Graham doesn’t provide any documentation to support Walker’s charge. Nonetheless, Graham is clearer than any other scholar about the relationship shared by the two writers, but we still don’t know the precise reason for their estrangement.

By the time Wright’s watershed novel appeared in 1940, Walker had left Chicago to pursue a master’s degree at the University of Iowa. She graduated that August having completed the volume For My People, for which she received the prestigious Yale Series of Younger Poets award. It was one of the two peaks of her artistic career. The second was the publication of Jubilee in 1966, by which time she was a wife, mother of four, holder of a PhD from Northwestern, and a dynamic professor at Jackson State College in Mississippi. She was also on the way to becoming a litigant, as she brought a plagiarism suit against Alex Haley, charging that Haley drew explicitly from Jubilee to write Roots. Graham documents how Haley was eventually discredited, though Walker lost the lawsuit. In fact, she seems to be the only one who sued Haley who lost even though her case was as strong as any other.

Over the closing decades of her career, Walker was a restless creative, formidable intellect, and indefatigable institution builder. She planned more creative works than she could possibly complete, penned voluminous political commentary, and built the institute that now stands as the Margaret Walker Center at Jackson State University. Graham covers all this in painstaking detail as she rounds out the best portrait of Walker and the fullest description of the metaphorical Walker house—a space constructed with religion, radicalism, humanism, and proto-feminism—that we are likely to get. This book is adroit, even brilliant, befitting its subject.